|

| Sprunston, just south of Durdar, near Carlisle |

Margaret was the daughter of the

foreman at the nearby chalk quarries and had worked for the Pallister family

only from 9th June; she was regarded as an intelligent girl who was

engaged to look after the three children and do minor household chores. They

had one other servant, a lad called George Haffen, who did farm work.

At about 8am on 2nd

July Mr. and Mrs. Pallister left the children, Margaret Hodgson (5yrs) and an

infant Mary Elizabeth Pallister, in the care of Margaret while they went into

Carlisle. She was instructed to strictly care for the children and not to do

any work. George was working in a field approximately 100 yards from the house

hoeing potatoes, and at about 10am he heard the baby cry, which he placed

little importance to. Shortly, five-year-old Margaret Hodgson, the oldest

child, shouted that he had to come, saying a man had taken the baby. He then

spoke to Margaret Messenger who repeated this account saying the man had left and went in the

direction of the orchard and well. He himself thought they were joking, but

checked and found no man, nor any sight of the child. He continued with his

work. About half an hour later he then saw Margaret Messenger carrying the body

of the infant across a field called Lamb Close, with the five-year-old

following her. It was now around 11:30am and a neighbour called Mrs. Story, was

quickly called from her house 300 yards away. She found Margaret Messenger

stood over the body in a yard and also noticed the front of the body was dirty

and wet, but the back was dry; the body was still warm to touch. She asked

Messenger what had happened and was told the same account of the man by her.

When asked, she added that the baby was found near the well in a pool with a

big stone on top of its head. Mrs. Story accused her of lying, saying that she

had done this. Mr. Story had returned from Carlisle and guarded her in the

house, which he had now locked her in. He also questioned Messenger she now

stated that she had fallen asleep while nursing the child in the Lamb Close

field and when she woke the child was not there. This further alerted his

suspicions as the child could not have walked to where it was ‘found’ by

Messenger. She showed him the place, which was a boggy piece of ground just

below the well. He confronted her, stating that there were a lot of footprints

of her clogs, but none made by any man, and a mark existed where a stone had

been lifted, with further clog marks of hers present at that location. She then

burst out crying, saying she would tell him the truth, but he warned her to

keep it for the authorities. The Pallister’s later returned to learn of this

second tragic death of another child.

Superintendent Sempill was called

and attended at 6pm. He asked Mrs. Story to retrieve the clogs and clothing

worn by Messenger that day. She went with the servant to her room and asked her

to tell her the truth. After hesitating, Margaret Messenger then admitted that

she had done this terrible deed. The Superintendent was called to the room and

Mrs Story told Messenger to repeat to him what she had told her. The

Superintendent realised something significant would be said and cautioned her; she then repeated her admission to causing the death of the infant, which he

took down into writing. She stated that she had put the child in the bog and no

one helped her. He then had plaster casts made of the clog prints near the

scene, for later production at court as evidence. Margaret Messenger was then

arrested on suspicion of murder.

On Monday 4th July an

inquest was commenced at the family home, but adjourned, awaiting the result of

the post-mortem. Messenger was further remanded by the magistrates after the

inquest adjournment. Doctors. Moffat and Brown conducted a post-mortem and were

able to later state that the cause of death was suffocation when immersed in

mud. The inquest was reconvened on Monday 11th at The White Quey

Inn, Durdar and the verdict was one of Murder of the infant. She remained on

remand at the gaol and her mother allowed to pay her a visit.

The trial took place at the

Assizes court which sat on Wednesday 2nd November 1881 and the above

evidence was given. Mr. Page was one of the prosecuting barristers and then

went on to outline the possible defences to a charge of murder. Three were

quickly discounted as not feasible:

·

If a man took the child where were his

footprints?

·

The child could have fallen into the pool and

drowned, but no water was in the lungs.

·

If the child had fallen from someone’s arms into

the bog, who had carried it there? If it were the prisoner, why had she not

merely lifted it back out?

He then paid particular attention

to a fourth defence in that it had not been proved that the child had Guilty

Knowledge’. He had earlier spoken at the start of the trial on this subject. A

person under seven years could not have such Guilty Knowledge to commit a

crime, neither could a child between seven and fourteen but in this older child

that was only a prima facie presumption that could be rebutted, if such Guilty

Knowledge could be shown. Had the child done the deed and then openly stated

she had killed the infant then Guilty Knowledge would be difficult to show. In

this case a murder had taken place and means had been used to prevent the truth

being found out. The question for the jury was one whether this constituted

that Guilty Knowledge to what she was doing was wrong.

The Messenger family were from

the parish of Rosley, near Wigton, and the vicar and also the schoolteacher

gave good character references for Margaret as an attentive and kindly girl,

the schoolmaster had placed her in charge of his own children.

There then followed a spirited

plea to the jury by the defence, before the judge summarised the case. He

reminded the jury it was not their prerogative to show mercy, but that it was

their sworn duty to ensure justice was done, based upon the evidence presented.

He then summarised the evidence, touching on the issue of possible motives and

defences. The jury retired for only ten minutes and returned to the courtroom

with a verdict of Guilty with a plea to mercy on account of her age. The

learned judge then had a terrible duty to perform, for there was only one

sentence he could pass. He donned the black cap and said:

‘Margaret Messenger, you have

been found Guilty, after a very careful and long trial, of the heinous crime of

murder. Your life is now at the mercy of the Queen’s prerogative alone. I shall

not prolong the misery, agony, and pain of you and all who have heard this case

by one word of reproach to you. My solemn oath is to pass upon you the dread

sentence of the law. That is, that you be taken hence to the place from whence

you came, and from thence to the place of execution, and there to be hanged by

the neck until you are dead, and that your body be afterwards buried in the

precincts of the prison in which you shall have been last confined after your

conviction, and may the Lord have mercy on your soul.’

The judge himself was much

affected by the sentence he had to pass on this fourteen-year-old girl.

Margaret was removed to the goal and appeals were submitted to the Home Office,

for consideration by the Crown. The early appeal pointed out that Margaret now

showed remorse for her deeds and had written a letter to Mr. and Mrs. Pallister

for murdering two of their children, saying also that God had forgiven her as

she now hoped they would also. She also said that she hoped a new servant would

serve them better than she had done. She

was examined by Dr. Orange, of the Broadmoor Asylum and Dr. MacDougall, the

Carlisle Gaol surgeon, with a view to ascertain her state of mind. Dr. Orange

reported to the Home Office and on Tuesday 13th December Mr.

Haverfield, the Carlisle Gaol Governor, received that commutation of the death

sentence to one of penal servitude for life.

The Messenger family had lived at

Chalk Foot, Cumdivock, between Curthwaite and Dalston; Margaret was born there

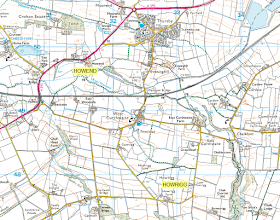

in 1867 and spent her childhood in that area. After penal servitude she was

released in December 1891 from Woking prison and is then known to have lived

with her younger brothers, George and Joseph, at Howrigg, at Woodside, Rosley,

and was employed as a dressmaker. In 1939 she is known to be living about a

mile from that location at Howend Cottages, Thursby, now on her own. It is

believed she lived to the age of 91, dying as a spinster in 1959 in the Wigton

area, which Howend would be part of.

Further information has been volunteered from local people and the house is believed to have been the second one at Howend, as you travel towards Thursby roundabout, from Cockermouth. It was said that the only book she read was the Holy Bible. Children who passed on the way to school were told to hurry by her house, which they did, but never knew why.

Further information has been volunteered from local people and the house is believed to have been the second one at Howend, as you travel towards Thursby roundabout, from Cockermouth. It was said that the only book she read was the Holy Bible. Children who passed on the way to school were told to hurry by her house, which they did, but never knew why.

|

| Howrigg and Howend, near Thursby, west of Carlisle. |

©opyright