|

| St. Bees Head Lighthouse, by W.H. Bartlett, drawn in 1842 |

There has been a lighthouse at St. Bees Head since 1718 and it was the last one to be lit by coal fire, which was highly inefficient, requiring a lot of maintenance and supervision. It was high on the cliffs of St. Bees Head with only Tarnflat farm as the only building that was in view from the premise, at a distance of roughly half a mile. In 1822 the keeper of the remote lighthouse was William Clark; he was married to Mary, who was by then 32 years old and they had five children, with Mary also pregnant with a sixth. The oldest was Christine (or Christina) who was 12 years old, then Isaac (9), John (7), Jane (5), and James (3). The Clark family had a routine of visiting Tarnflat each morning and evening to obtain their milk from the farmer. On Thursday 17th January William had gone into Whitehaven, which was about three miles away, for the purpose of visiting the market, and was accompanied by his 12 year old daughter. (Copied burial records suggest the oldest was a son called Christian, but news reports state William went to Whitehaven with his 12 year old daughter, not a son, so I have assumed the burial record was not very legible and was incorrectly copied as 'Christian'. Due to current COVID restrictions I am unable to fully verify). On his return that evening he was perfectly sober and made his way back to his home.

The first hint of something unusual came about when no member of the family had gone to Tarnflat farm for the Friday morning milk supply but no great concern was initially attached to this anomaly. Later that evening however the farmer realised that the beacon of the lighthouse was not lit. That was a serious concern to him, as he knew this was something William would never neglect to do. Due to this, the farmer and others went to the lighthouse and found the place locked, with a strong smell of smoke emanating from the premise. Despite their constant banging on the door they could raise no-one. Fearing the worst, they forced their way in and found Mary with four of her five children all unmoving, and in the same curtain sided bed; strangely none of these bed curtains had caught alight. There had clearly been a fire within the premise and the occupants of the bed were all dead. Only the youngest suffered burn marks to its leg, from the ankle to the knee; the fifth child was in a room above and had also died from smoke inhalation. William himself was lying on the floor and was alive, yet insensible. He was also burned on his right arm and down the right side of his torso; it was supposed that the draft of air from under the door had been sufficient to maintain his life, but it was despaired that he would succumb to his injuries.

An inquest was held at Tarnflat the next day, Saturday 19th, by the coroner Peter Hodgson Esq., in the presence of a jury. The above circumstances were inquired into and the court had been unable to establish a time of the incident. It was supposed that the fire had commenced following a spark from the beacon coal fire having caught in the clothing of the father and somehow had begun smouldering when all the family were asleep. Had anyone been awake it was supposed would have aroused all the others. A verdict of 'Death by Suffocation' was returned by the jury.

Mary Clark and all her children were interred at St. Bees churchyard on Sunday 20th, a great crowd of local people attended to pay their respects, moved by the tragic circumstances of the whole loss of a family, with the exception of the father.

The newspapers reported that William, against all medical expectations, began to recover. He recalled only that some of the children appeared to be sick, likely from the smoke of the fire, but could offer nothing as to the cause of the fire itself. No doubt this account was formed following his rousing, before he himself succumbed to the smoke and he fell into unconsciousness. Although the community were relieved at William's continued recovery they feared for what kind of life he would live from then on. He was known to be a loving, caring husband and father, but was now bereft of the whole of his family.

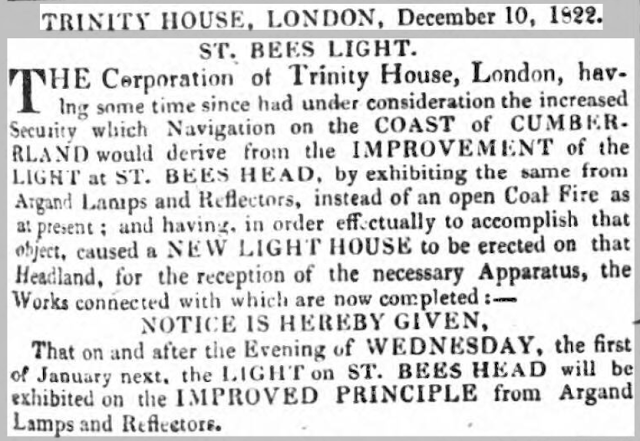

The tragedy finally brought about change of the beacon for the improved safety of the seafarers plying there inherently dangerous trade along the Cumbrian coast. The corporation of Trinity House, London, caused the erection of a new lighthouse for the purpose of exhibiting the new Argand lamp and reflectors. It was reported in mid December that the first showing of the new light was expected to be on Wednesday 1st January 1823. This device had been patented in 1784 by the Swiss inventor, Aime Argand, and was an oil burner which utilised a wick between two metal tubes, the light of which was reflected to sea. The use of this system meant that navigators of the Solway Firth entrance could see both the St. Bees light and the one on Douglas Pier when passing between them, creating a far safer journey for both the vessel crews and their vital cargoes and passengers.

No comments:

Post a Comment